Compare courses from top Australian unis, TAFEs and other training organisations.

Studying Ain’t What It Used to Be – It’s Better

If the word ‘study’ prompts memories of boring lectures and awkward tutorials then you’re not alone – but you are out of date. Study has changed rapidly over the last two decades and Marni investigates the major developments.

Marni Williams

Apr 13, 2015

Think back to when you were last at TAFE or university. If it was more than 10 years ago, then it’s quite possible that memory involves a suited figure standing down the front, wrestling with an overcrowded PowerPoint that’s crying out for a graphic designer, and some of the longest hours of your life.

Maybe you loved every minute of those lectures – sure, I’ll never forget the time one of my lecturers decided to start our modern art course with a Dada performance that involved him wearing a bucket on his head – but maybe you’re also remembering all those times you nodded off in the dark, the frustration you felt at not being able to ask potentially embarrassing questions before the lecturer moved on to the next topic, or those awkward silences in tutorials when it was clear no one had done the reading.

If this is your impression of tertiary education, then you’re certainly not alone. But if you think that’s what you have to endure in order to get qualified these days, then I have good news for you: you’re behind the times.

Today’s students have demanded change

When does change start to become real? When the consumer demands it. Everyone these days expects technology to make their lives more convenient and their experiences to be richer, and that includes their education. Add those expectations to the greater prevalence of degrees and the increased competition in finding a job after graduation, and the old methods start to look just a little too dusty. The academic-led New Media Consortium has been tracking developments in education for over two decades, and their latest NMC Technology Outlook for Australian Tertiary Education indicates we’ve reached a tipping point:

‘As the workforce has evolved, calling for a mix of highly technical and communication-centric skill sets, student expectations of the traditional university degree are changing. There is less perceived value in large lecture hall courses and a greater emphasis on campus experiences that invoke more hands-on, immersive learning experiences that either simulate the real world or are part of it.’

I guess we all figure that if an algorithm can plan the perfect road trip, and we can tour the world’s museums or find our ancestors’ birth records from the comfort of our living rooms, then maybe traditional study has some catching up to do. But has it caught up? On one hand, the NMC suggests it has:

‘Over the past several years, there has been a shift in the perception of online learning to the point where its value is now well understood, with flexibility, ease of access, and the integration of sophisticated multimedia and technologies chief among the list of appeals.’

However, delivering courses online is really only the beginning: today’s technology is about much more than improved delivery methods. I’ve been tracking some of the most important changes that are making their way into the tertiary sector and some of them are so exciting they might just make you want to give it another go. And I promise you, we’re well past PowerPoint.

5 game-changing trends in education

1. Open learning

Open learning is all about getting resources and research out to as many people as possible, for free. While the term encompasses developments in sharing such as Creative Commons and the increase in open online journals, the hottest word on everyone’s lips in 2012 was MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses).

These hugely popular free online courses may not have brought traditional university models crashing down, but they certainly have given them cause to consider making their content more available. The NMC report says open content is ‘considered to be an extremely important topic in Australia’ and the government has even published guidelines and stipulated that certain government-funded research must be made accessible to everyone.

Some open-access pioneers include La Trobe University, which has piloted a program using Wikiversity and the Wikimedia Foundation Projects, and Adelaide University, which has transitioned its science textbooks from print to open-source.

Want to find open educational resources? Check out OER Commons.

2. MLearning

If we shop, bank, socialise, read and work from our mobile devices, then why shouldn’t we be able to learn from them in a formal way? It seems mobile learning is already making its way into our hands, as the NMC reports:

‘All three of these projects’ expert panels – a group of 145 acknowledged experts – strongly agree that mobile learning and online learning, in some form, will likely tip into mainstream use within the next year.’

Mobile learning not only allows learning to take place easily off campus and on-the-go, it allows students to work it in with traditional methods on an individual basis. For example, mobile learning has been used by Curtin University to deliver individual polls during class, testing each student’s understanding of the content in real time.

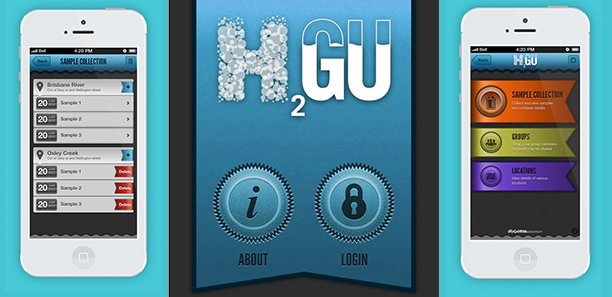

Practical lessons are also benefiting: Dr Peter Teasdale at Griffith University has developed an app called ‘H2GU’ to allow his students to collect and test water samples while in the field and medical students at the University of Melbourne are even managing patient records via their mobile devices while they make their rounds. As universities and TAFEs develop apps and make their existing sites mobile-friendly, stand by for more palm-based pedagogy.

3. Rich content for the flipped classroom

The concept of the flipped classroom is the next big step from blended learning, and, when combined with rich content such as audio and video, this reversal of the traditional lecture is proving to be popular with students.

Where blended learning allows students the flexibility of learning in their own time, the flipped classroom goes one step further: it not only provides online resources for students, it requires them to direct their own learning outside of class, leaving class time only for personal interactions such as practical training and discussion.

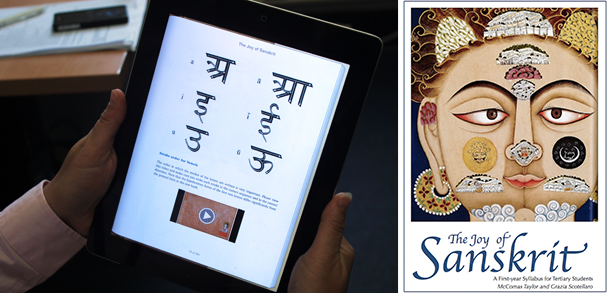

The School of Nursing and Midwifery at the University of Western Sydney has turned to the flipped classroom model in order to dedicate one hundred percent of face-to-face time to clinical practice. And for the Australian National University’s McComas Taylor, flipping his Sanskrit lessons over to an e-textbook has left more time for speaking (and chanting!) in the classroom. The inclusion of rich media has been a key development here: McComas’s students can replay snippets of video and sound recordings of individual Sanskrit words as they are spoken, allowing them to see and hear them over and over, in their own time, slowing them down to each syllable until they can understand and replicate them in class.

McComas’ e-textbook has been so successful that he can now claim to be the only academic to export the teaching of Sanskrit to students in India! And with all his rich media delivered in a mobile-friendly way, he has even reduced the time that needs to be spent on revisions as he has found his students remember almost all the previous semester’s content when they return after semester break – after all, they can simply play their lessons through their phones from the beach or the bus. That’s a pretty significant development for one of the world’s oldest living languages.

4. Gamification

Gaming culture has matured significantly in recent years, moving on from its origins in shoot ‘em ups to encompass strategy-focused quests and interactive tools for brain development (Lumosity challenge, anyone?). As games have become more mainstream, portable and pervasive, it’s only natural that they should extend to personal and professional development.

These days, games are used as training and team-building tools in the corporate world, where players (or employees) undertake goal-oriented learning and find themselves rewarded with incentives or recognition in the form of badges and leader boards. It’s becoming a wider reality in the education sector, too, where institutions are beginning to understand the value of games for cross-curricular teaching and providing their students with avenues for role playing. The NMC says a widespread adoption of gamification by educators is close:

‘Both the 2014 Australian panel and Global Higher Education panel agree that games and gamification are gaining traction in teaching and learning, but expect it will take two to three years to fully come to fruition.’

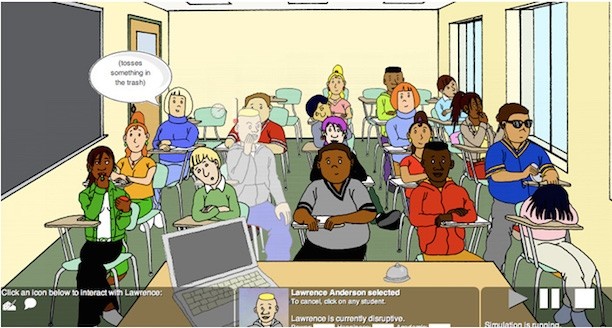

Some trailblazing examples include Curtin University’s simSchool, where teachers can practice delivering lessons in a virtual environment and interact with simulated students, and Griffith University’s World Trade Game, which is an online multi-player experience that teaches students the economic and environmental impacts of global trading.

Even some MOOCs providers, including Swinburne Online, are taking a leaf out of the gaming handbook, incentivising their successful graduates with ‘badges’ or ‘micro-credits’ that are recognised through Mozilla’s Open Badge Initiative (OBI). If professionals start racking up these badges like they attract LinkedIn recommendations, then it’s possible that MOOCs and other short courses may start to offer more tangible career benefits.

5. Learning analytics

The final innovation on my shortlist holds the most potential to disrupt our already-disrupted experience of study: mining big data for big insights. Now that substantial proportion of learning is happening online, institutions are able to track the intricacies of individual student interactions. Learning when a student is most engaged and, more importantly, when and why they give up, could just take education in as-yet-unimagined directions.

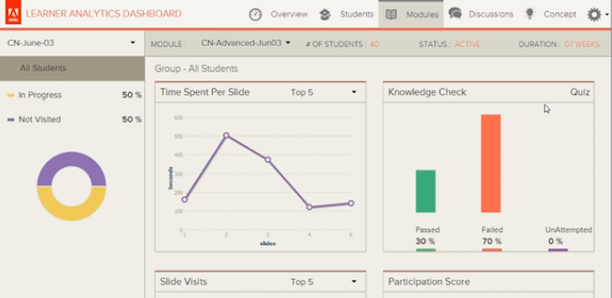

The NMC has declared widespread adoption of learning analytics in Australia as ‘two-to-three years away’, but researchers from the University of Newcastle and Murdoch University are already pooling their results for greater insights. Learner Management Systems have been rolled out across the country and Adobe are even including analytics as part of their Presenter software.

The potential for this knowledge to further revolutionise learning is huge. Once it’s clear how students engage with platforms and ideas, there is the opportunity for institutions to develop tools and algorithms to deliver more responsive and personalised learning experiences – if your tutor was as good as Facebook is at anticipating your desired content, then learning may just become hard to resist!

The challenges

There are still a few roadblocks in the way before we see all of these elements working together to offer a more personalised and interactive form of mainstream education, but they are certainly making some waves. The reality of the moment is that the sector is facing outdated funding models and increased focus on employment outcomes, so the pressure is coming from a number of directions. The NMC has singled out ‘low digital fluency among educators’; ‘the ability to scale teaching innovations’; and ‘keeping education relevant’ as the biggest challenges facing tertiary education at the moment. To my thinking, the three issues go hand-in-hand, and if surmounted, we might just find ourselves on the cusp of a more equitable and engaging way of learning.

Want to see what’s out there in online learning? Find an online course you like and make an enquiry to find out more.

About the author

Marni Williams provides tips on career progression, job applications, and educational pathways at Career FAQs.

Categories